Robert H. Brooks, born October 8, 1915, was the first U.S. Armored Force Soldier killed in World War II. Brooks was a member of D Company, 192nd Tank Battalion.

By Rae Whitley, Assistant Curator, National Museum of Military Vehicles

PFC Robert H. Brooks, the first U.S. Armored Force Soldier killed in World War II

Fort Knox was the former home of the U.S. Army's Armor School. From 1940 to 2011, armored crewmembers were trained in their skills as they maneuvered the Kentucky countryside. Soldiers graduated from their training in ceremonies steeped with tradition while proudly marching across parade fields.

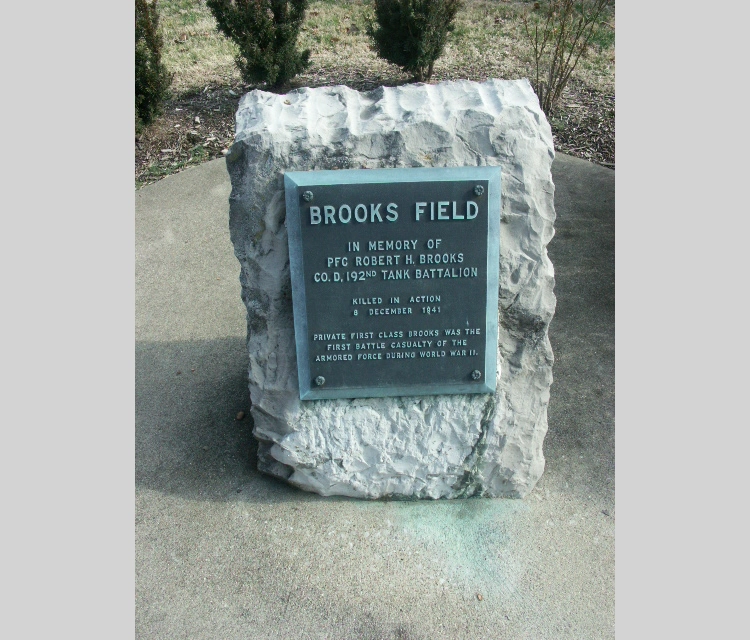

One such parade field at Fort Knox is Brooks Field, the largest contiguous parade field in the U.S. Army. Brooks Field was dedicated on December 23, 1941, in honor of PFC Robert H. Brooks, the first U.S. Armored Force Soldier killed in WWII. Unknown until the time of the dedication was the fact that Brooks was an African American serving in an all-white unit.

Robert H. Brooks was born on October 8, 1915, in McFarland, Kentucky. As an adult, he moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, where he enlisted in the U.S. Army. His enlistment record shows Brooks stated he was Caucasian. To use a term of the era, he was "passing" to enlist. Robert was sent to Fort Knox, Kentucky for his training, and in 1941 became a member of D Company, 192nd Tank Battalion.

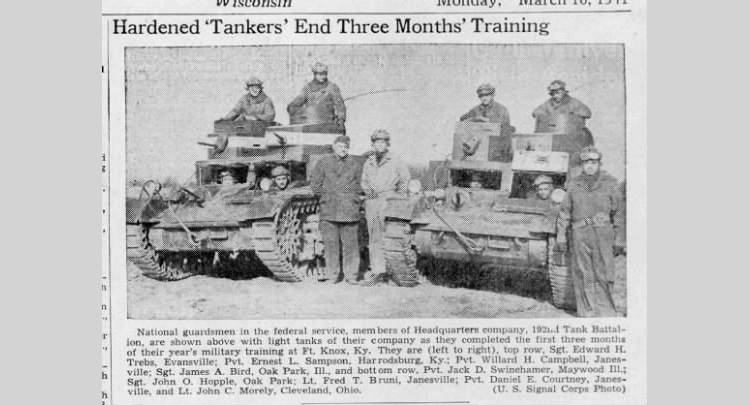

The 192nd would have basic and advanced training at Fort Knox while part of the 69th Tank Regiment of the 1st Armored Division. By late summer of 1941, the selectees of the 192nd were sent further south to participate in the Louisiana Maneuvers. These training exercises proved invaluable as the soldiers and their officers were able to improve their doctrine in simulated "war games". This would be the most important and last field exercise in their career. Unknown to them, the 192nd had already been scheduled to be sent to the Philippines.

After the maneuvers, in September 1941, the battalion was ordered to Camp Polk, Louisiana. There, the battalion learned that they were not being released from federal service. Instead, they were being sent overseas as part of "Operation PLUM." Within hours, many of the members of the battalion believed that they had figured out that PLUM stood for the Philippines, Luzon, Manila. Men who were married or 29 years old or older, had the opportunity to resign from federal service. Replacements for the men came from the 753rd Tank Battalion.

The 192nd arrived in Manila Bay on November 20 and were taken to Fort Stotsenburg. They were greeted by Gen. Edward P. King Jr. who apologized that they had to live in tents along the main road between the fort and Clark Airfield. Ironically, November 20 was the date that the National Guard members of the battalion had expected to be released from federal service.

The 192nd had many ham radio operators and within hours of arriving in the Philippines they had set up a communications tent. The members of the battalion sent radio messages home saying they had arrived in the Philippines safely. Ten days before the attack on Pearl Harbor, reconnaissance pilots reported that Japanese transports were milling around in a large circle in the South China Sea. On December 1, the tankers were ordered to the perimeter of Clark Field to guard against Japanese paratroopers. From this time on, two crew members always remained with each tank.

Radio operators in the 192nd's communications tent were the first to learn of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. The officers of the 192nd were called to the tent and informed of the news. All members of the tank and half-track crews were ordered to Clark Field to guard against Japanese paratroopers.

Around 8:00 A.M., the planes of the Army Air Corps took to the sky. At noon the planes landed and were lined up to be refueled near the pilots' mess hall. While the planes were being worked on, the pilots went to lunch. At 12:45 in the afternoon on December 8, 1941, the Japanese attacked Clark Field.

The tankers were eating lunch when planes approached the airfield from the north. At first, they thought the planes were American and counted 54 planes in formation. They then saw what looked like raindrops falling from the planes. It was only when bombs began exploding on the runways that the tankers knew the planes were Japanese. The tankers watched as American pilots attempted to get their planes off the ground. As they roared down the runway, Japanese fighters strafed the planes causing them to swerve, crash, and burn. Those that did get airborne were barely off the ground when they were hit. The planes exploded and crashed to the ground tumbling down the runways.

According to Morgan French, Robert was running to his half-track. It was the belief of the other members of the company that Robert was attempting to get to his half-track so he could man the .50 caliber machine gun on it. As he ran, a bomb, which was a dud, hit Robert and split him in two, and killed him instantly. Ralph Stine, who was looking through the viewing slot in his tank, watched the entire event. Robert was found by the other members of his company, with severe, fatal head injuries and part of his shoulder missing. Robert Brooks was the first American tank battalion member to be killed in World War II.

When the news of the death of PFC. Robert H. Brooks reached Fort Knox, the Commanding General, Jacob Devers, ordered that the main parade ground at the base from that day on be named after him. One of General Devers' aides attempted to reach Robert's parents in Sadieville, Kentucky. As it turned out, the bank had the only phone in the town. W. T. Warring at the bank answered the phone and was asked by the aide if he would help locate Robert's parents to attend the dedication ceremony.

The aide asked Mr. Warring if he could tell him anything about Robert's parents. Mr. Warring said, "His parents are tenant farmers, ordinary Black people." The general's representative hung up the phone and immediately called back. He said to Mr. Warring, "Did you say they were Black?" Warring responded, "Yes, his mother and father are very dark." The aide felt that this might change the situation. When he reported back to General Devers, the general said, "It does not matter whether or not Robert was Black, what mattered was that he had given his life for his country."

Excerpt from the dedication ceremony speech:

"On December 8, the first day that America entered the war, PFC. Robert H. Brooks died on the battlefield near Fort Stotsenburg, in the Philippine Islands. For him, the first soldier of the Armored Force to be killed in action, this parade ground, with its flag now at half-mast, will be named Brooks Field."

"In death, there is no grade or rank. And in this greatest democracy the world has ever known, neither riches nor poverty, neither creed nor race, draws a line of demarcation in this hour of national crisis."

~ General Jacob Devers, December 23, 1941